July 23, 2014

Who Pissed Off Ogopogo?

Shaken. Rattled. Disoriented. Exhausted. Unnerved.

Some of the adjectives used by swimmers after their swim.

The 2014 version of the largest and oldest open water swim in Canada was daunting if not outright discouraging for most of the swimmers who started the 2.1km event at the Old Ferry Wharf jetty. Usually, 90 minutes (the normal time cutoff to complete the swim) is more than enough for the majority of swimmers to make the crossing. Yet, on this day, less than half of all the starters had finished the swim within 90 minutes; and only 490 swimmers had completed it after two hours of swimming. Many swimmers took more than twice as long as expected to complete their journey; the last two swimmers that finished took over 3 hours to complete the swim. Even the best felt like they were in an endless pool, making no headway despite their well-trained strokes. Clearly this was an Interior Savings Across the Lake Swim like few others before it, although a record number of swimmers still completed the swim.

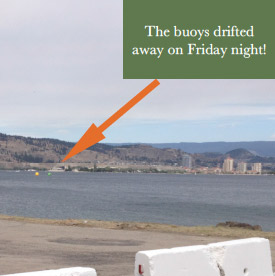

So, what happened? Despite the weather forecast for gusty winds, and a threatening Smith Creek interface fire nearby that had already caused the evacuation of thousands, the swim started in apparently calm waters on a cool smoke-free morning. The day before, the strong winds had de-anchored the starting line buoys that had been set in place, sending them quickly into the middle of the lake (see image on right). Before the start, WFN Elder Grouse Barnes had provided a blessing for safe passage to all of our swimmers, while providing a prescient message that swimmers would be passing through Ogopogo’s kitchen (known as n’ha-a-itk in Salish tongue – good luck trying to say it!). Starter Nick Rabinovitch set off all 9 waves on time, and from the jetty a nice straight procession of swimmers to the finish line was observed.

So, what happened? Despite the weather forecast for gusty winds, and a threatening Smith Creek interface fire nearby that had already caused the evacuation of thousands, the swim started in apparently calm waters on a cool smoke-free morning. The day before, the strong winds had de-anchored the starting line buoys that had been set in place, sending them quickly into the middle of the lake (see image on right). Before the start, WFN Elder Grouse Barnes had provided a blessing for safe passage to all of our swimmers, while providing a prescient message that swimmers would be passing through Ogopogo’s kitchen (known as n’ha-a-itk in Salish tongue – good luck trying to say it!). Starter Nick Rabinovitch set off all 9 waves on time, and from the jetty a nice straight procession of swimmers to the finish line was observed.

The finish line had a different feel to it than in previous years, with swimmers feeling grateful that they were able to finish, but having to dig much deeper into their physical and psychological reserves than they expected to. Many looked at their watches or the timing clock in disbelief, thinking that something had malfunctioned, and concerned supporters were looking for their overdue friends and family. Organizers found themselves in a situation where they had to prolong the event, coordinate the safe return of assisted swimmers, provide information to supporters and continue to ensure safety for all.

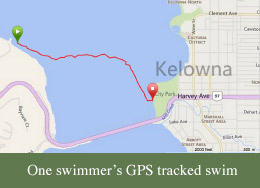

The wind was barely noticeable and there were no significant waves the morning of the swim but something was felt by the swimmers half way across the lake, pushing them toward the Delta Grand Hotel and Tugboat Beach, more than a kilometre north of the finish line. It felt like swimming up river for every participant who commented on their experience, substantially increasing their time in the water, causing cramps for many and exhausting most. The 20 power boats and 50 lifeguards started offering swimmers a ride to the finish around the 2 hour mark, with many making the wise decision to accept the support and not endanger their safety. In total, almost 200 swimmers accepted the help offered, the highest number ever (in comparison, in 2013 no swimmers were brought to the finish line, and in 2012 there were only 10). Anybody who swam 2 hours or longer on Saturday should be proud of the perseverance and endurance they showed. Many swimmers commented: “Who pissed off Ogopogo?”

The wind was barely noticeable and there were no significant waves the morning of the swim but something was felt by the swimmers half way across the lake, pushing them toward the Delta Grand Hotel and Tugboat Beach, more than a kilometre north of the finish line. It felt like swimming up river for every participant who commented on their experience, substantially increasing their time in the water, causing cramps for many and exhausting most. The 20 power boats and 50 lifeguards started offering swimmers a ride to the finish around the 2 hour mark, with many making the wise decision to accept the support and not endanger their safety. In total, almost 200 swimmers accepted the help offered, the highest number ever (in comparison, in 2013 no swimmers were brought to the finish line, and in 2012 there were only 10). Anybody who swam 2 hours or longer on Saturday should be proud of the perseverance and endurance they showed. Many swimmers commented: “Who pissed off Ogopogo?”

So what would have caused the swimmers to be pushed so far north when there were no significant waves or wind? Was it really Ogopogo? We did some research and discovered the phenomenon of a Seiche wave. In short, a Seiche wave is a stationary wave in a body of water caused by a change in several factors including atmospheric pressure, seismic activity and wind. Hmm, wind? We know there was significant wind the days and night before the swim. In fact, when we arrived in the morning at 4am to set up, the wind was very strong, then at 6am it suddenly stopped. Could this have caused a Seiche wave? We came up with a theory:

The strong and sustained winds running parallel along the long narrow shape of the lake days prior to and the morning of the swim created a current running north. The narrow point of the lake where the ATLS occurs (near the Bennett Bridge) focused the wave/current to be stronger there. The bridge itself further narrowed the opening increasing its velocity. This Seiche wave pushed the swimmers north up the lake.

We needed validation of our theory so we looked for someone who is a specialist in Limnology and found an expert at the University of British Columbia Okanagan. We contacted Dr. Ian R. Walker, Earth & Environmental Sciences and Biology and ran our theory past him. He confirmed: “It is quite likely that a seiche was operating at the time of the swim. The potential for strong seiche-induced currents at the floating bridge is exacerbated by three things: 1) The bridge approximates the midpoint of the lake, 2) The lake is much narrower at the bridge than along much of the lake’s north-south axis, and 3) The lake is much shallower at the bridge than throughout almost the lake’s entire length. As a consequence there is potential for large volumes of water being directed through the constriction at the bridge during seiche events, producing strong currents.”

And there you have it. A disturbance in the lake water produced by high winds caused a Seiche wave which carried the swimmers north, even though there was little wind or waves during the actual swim. What seemed like perfect swimming conditions above, were hiding a strong current below.

Huge thanks to Nick Rabinovitch for conducting this research.

Open water swimming is always dependent on weather by its very nature and can abruptly change any expectations of a finishing time. Training our swim skills and being comfortable in all conditions is as important as a healthy reserve of fitness and mental stamina to deal with these uncontrollable variables. Staying relaxed, and trusting the warmth and floatation of your wetsuit remain the anchors of success.

For us as organizers, having sufficient support and an extraction plan for worst case scenarios remains crucial to a safe event, even when it may be under-utilized in most years.

And for all of us, we are reminded of the power of nature, and the capabilities of a large body of water that seems often so passive, yet unpredictable and dynamic within minutes.

The Interior Savings Across the Lake Swim organizers hope that ATLS 2014 will serve as a constructive learning experience for all of us, to redouble our collective commitment to develop skills in open water swimming. We hope you will all be back to pick up where you left off, probably shaving minutes, if not hours, off your 2014 swim times!